Editor's note: Tune in May 12 at 7:00 for the first Past, Present, and Future of Striped Bass, a Chesapeake Bay Perspective, an informative and educational series appearing on the FishTalk Facebook and YouTube channels, created by CCA-MD and hosted by Lenny Rudow and FishTalk to engage Chesapeake anglers in our current fisheries issues. Go to Preregister, and we’ll send you an email reminder and link before the broadcast.

Like I said in last month’s Fishery Issues Part I article: I’m not a scientist and I don’t play one on TV. So, as we discuss the current state of the striped bass fishery I’ll strive to not surmise, suspect, predict, or opinionate without always letting you know when that’s the case. Then you’ll know what is opinion (which should always be questioned when undertaking a scientific discussion) versus what is established fact (which should be given maximum weight in said discussions). Right? Well… Therein lies the rub.

Fact: We know striped bass numbers have dropped up and down the coast and in the Chesapeake Bay in recent years. There’s overwhelming evidence ranging from catch reports to surveys to young-of-year (YOY) reports, culminating in the Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) 2018 benchmark stock assessment. But beyond this, much of what we “know” is far from scientific or factual, and hard to mesh with the management system.

In a society that seems to have become okay with alternate facts and science denial, it may not come as any surprise that the facts and science used in striped bass fisheries management is something short of ideal. In fact, it’s probably a whole lot worse than you think. Still, we need to put a fishery stock assessment into context. We’re talking about an attempt to count all the fish in the sea, which is obviously impossible. So, we use the best science we have to make the best guess we can. Another fact: fisheries managers are forced, by law, to use the “best available science,” even when that science is, well, trash.

Opinion: this “best available” standard can lead to what some might consider complacency with the use of questionable data. One glaring example comes from management’s use of the nine-percent mortality figure when assessing how many stripers recreational anglers accidentally kill while catching and releasing fish. Does catching and releasing rockfish really result in nine-percent mortality? The citations regarding this mortality rate go to a 1996 study (Diodate and Richards) performed on fish caught and released in a saltwater pond in Massachusetts. The study was performed during the middle of summer, with surface temperatures reaching as high as 82 degrees. There were no controls regarding angler experience level, type of hook used, or type of gear used. This study was not designed to ascertain a reliable figure for a coastwide mortality average, and in its final paragraph the scientists who performed it specifically state “Our present model would not be sufficient for estimating coastwide hooking mortality of striped bass…” Yet that’s exactly what fisheries managers do, while citing it as the “best available science.”

Why not design a modern study to nail down striped bass catch and release mortality with confidence, accounting for different variables and situations? We have the tech to do so, but this is the wrong question to be asking. The right question is, who’s going to pay for it?

Fact: The science we base our striped bass fisheries management on is questionable at best, and laughable at worst. We. Need. Better. Science.

Striper Numbers

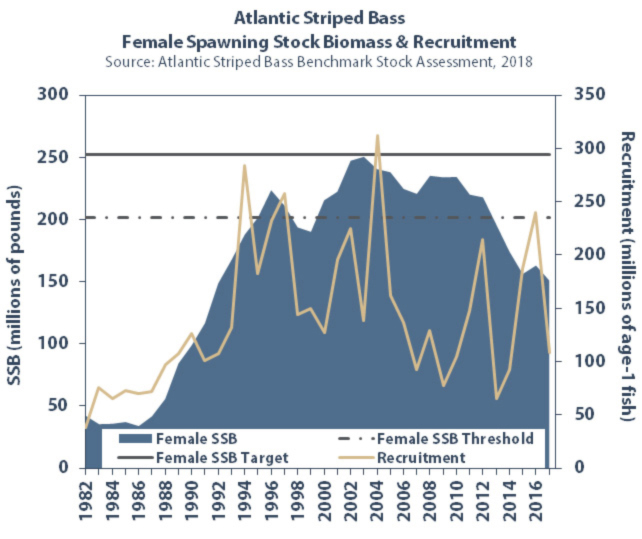

Unfortunately, at this moment in 2022 we’re stuck with the science we have. So, let’s get back to guessing at just how many fish are in the sea. According to the 2018 stock assessment, female spawning stock biomass (SSB) was estimated to be 151 million pounds. The threshold (a border between an overfished fishery and one that’s not overfished) for SSB is considered by the ASMFC to be 202 million pounds, which is where it sat in 1995 when the species was declared “recovered,” five years after the moratorium was lifted.

We often see doom-and-gloom social media posts lamenting the recent population declines and calling for immediate moratoriums on striped bass fishing. According to the ASMFC assessments in the 1982 to 1988 period, when the striped bass population was as low as has been estimated in modern history, the SSB was said to be below 50 million pounds. So, if you accept the stock assessment estimates, the rockfish population is currently over three times what it was the last time a moratorium was put in place. In fact, it’s over 50 percent more than when the previous moratorium was lifted, much less when it was initiated.

Now, here’s a bit of neither fact nor opinion but instead a personal observation: most of the people who are looking for a moratorium to be initiated today are anglers of the generation accustomed to incredibly strong stocks and incredibly good fishing. They don’t remember the bad old days of the 80s because they either weren’t alive or weren’t fishing back them. So from their frame of reference, it naturally seems as though rockfish numbers have never been anywhere near this bad before.

Since we managed to rebuild the stocks in a rather epic fashion after the moratorium ended with 50 percent less fish than we (think we) have now, it stands to reason that we can rebuild the stocks again without imposing a new one. Meanwhile, a full and complete moratorium would do tremendous harm to a huge number of people who depend on the fishery. Might other wiser and even more effective management methods be possible?

An Elusive Answer

Current management only takes one factor affecting the fishery into account: how many fish (we think) we directly remove from the stock. One has to wonder what would happen if we could also “manage” environmental factors. How the stocks might explode if we could drastically improve water quality, quadruple the number of menhaden in the Bay, and/or restore its oyster populations? We have to ask if the best way to rebuild the rockfish population is to take fewer fish out of the water, or if it’s to restore the water itself. Restore it to conditions that allow the fish to spawn successfully, thrive, and grow.

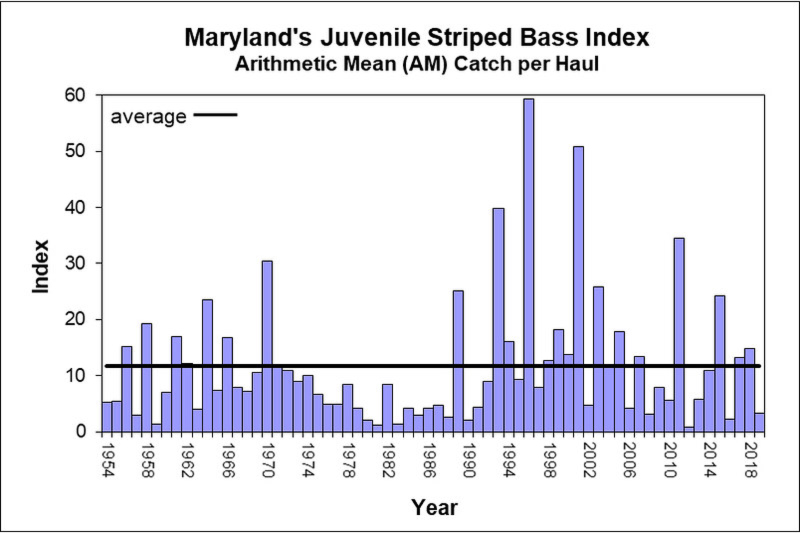

Environmental conditions have a massive impact on yearly spawning success, and while we know from the past that relatively low numbers of fish can produce huge numbers of offspring, we also know that huge numbers of breeding fish can produce very low numbers of offspring. A glance at a graph of the young of year (YOY) index makes it obvious that from one year to the next we can see a dismal spawn, followed by a spectacular spawn, followed by another dismal one, regardless of stock size. An even sadder fact is exposed when one looks at the spawning success recorded in the past few years. In 2019, 2020, and 2021, the YOY index for Maryland waters sat at less than half of the long-term average. Ouch.

Fishery Management Models

Food for thought: we can look to two collapsed fisheries that were rebuilt during a similar timeframe, rockfish and redfish, for comparative examples. When the rock were decimated we imposed a five-year moratorium followed by several years of heavy restriction. The fishery thrived for a couple of decades before the current downturn. In the case of redfish, rather than a moratorium a slot limit was imposed. Breeding stock became perpetually protected. The fishery thrived and continues to thrive today.

Might we learn something from that? Might a slot limit work a whole lot better than on-again, off-again complete protection? Most of the member states of the ASMFC seem to have come to that conclusion. Slot limits are currently in effect up and down the coast, including in Maryland’s Atlantic, though not in Maryland’s portion of the Chesapeake Bay nor in the Potomac River. In these places, we still allow 40-plus-inch fish to be harvested.

This brings us back to that release mortality figure. What good is a slot limit, if we’re catching and releasing so dang many fish that we kill a huge number of breeders anyway? Or, is killing those fish even the issue we should be focused on? One has to wonder, if they’re caught and released in pre-spawn months, could we be causing enough trauma to interrupt successful spawning? Who the heck knows — even with all of our high-tech modern medicine, we still can’t always control human reproduction. Natural reproduction in any species is unpredictable. But not only are we unable to answer the above questions, we can’t even make a reasonable best guess based on facts. We. Need. Better. Science.

That science is there for the taking. The next “best science” is one study away. Managers, stakeholders, and academia could team up to initiate gathering the facts we need to better answer all of these questions. And the know-how to do so does exist. But studies cost money, and fish, even those as vaunted as the striped bass, rarely get priority as the pie gets cut.

Management Actions

Let’s consider a few more of the few facts we do know: In 2020, the state of Maryland chose to reduce commercial catch by 1.8 percent while reducing recreational catch by 20 percent. Using that nine percent release mortality figure, the state then eliminated preseason catch-and-release fishing and claimed a net reduction of 600,000 dead fish. Can I get an LOL, people? Does anyone really believe that 10,000 rockfish a day were being caught and released in Maryland waters through the months of March and April, prior to the trophy season opening up? And that nine percent of those mythical fish died after being released? Note that one of Maryland’s own studies (Recreational Catch-and-Release Mortality Research in Maryland, Lukacovic), showed a 1.6 percent mortality rate during spring fishing in water under 59-degrees using single-hook artificial lures.

The mandatory use of circle hooks was also used to reduce mortality on paper by many ASMFC member states. At this point I feel safe saying that these well-intended regulations are a flop. I do not have scientific data to back up this assertion, but I’d wager that 90-plus-percent of the well-meaning live-liners and chummers out there can remember wincing as they dug a circle hook out of the guts of a blood-streaming 18-inch rockfish last summer. I don’t know if it’s due to changes in gear, changes in the fishery, or what, but the (decades old) studies showing the deep-hook reductions with circle hook use have not panned out during real-world use by the masses in modern times. Yet on paper, these regulations have vastly reduced the number of striped bass taken out of the gene pool.

The Bottom Line

The Facts: Rockfish numbers are down. The best guesses of fisheries scientists and regulators indicate that they’re around half of what they were at their peak in the early 2000s, but more than triple what they were at the trough in the mid-80s. Regulatory measures have been tightened as a result, but spawning success has been utterly dismal during the same timeframe.

Meanwhile, fishing for striped bass continues to be regulated through “best available” science that is laughable, combined with a healthy dose of political interests. And the way that the law and the regulatory structure are established, there’s only one thing that will ever change this. We. Need. Better. Science.

What You Can Do

Although recent experience would indicate that some folks in government utterly ignore everything we have to say as a recreational angling community, we’ve certainly seen some other government folks ask for and seriously consider our input. Thus, we still need to make our voices heard at every opportunity. Give your comments during each and every public comment period, and show up at the public meetings. We need to let the powers that be know just how many of us are hopping mad at how the striped bass fishery has been managed — and that we demand better science.

MOST IMPORTANT RIGHT NOW: Tune in May 12 at 7:00 for the Past, Present, and Future of Striped Bass, a Chesapeake Bay Perspective, an informative and educational series appearing on the FishTalk Facebook and YouTube channels, hosted by Lenny Rudow and FishTalk to engage Chesapeake anglers in our current fisheries issues. Go to Preregister, and we’ll send you an email reminder and link before the broadcast.

- By Lenny Rudow