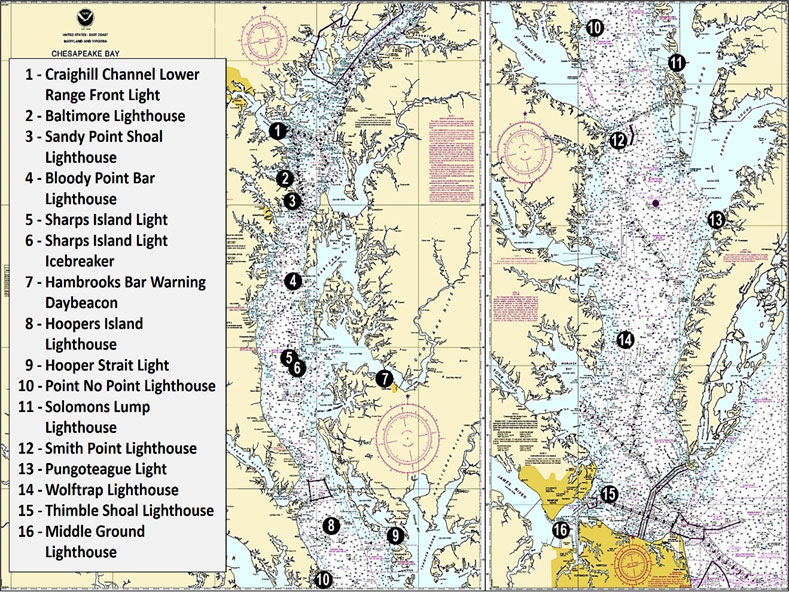

Anyone who's been Chesapeake Bay fishing has almost certainly seen a lighthouse or two along the way. Chances are you’ve never caught a Chesapeake Bay “sand hog,” though. That’s because it’s a slang term for manual laborers who worked inside subsurface pressurized chambers, hand-shoveling sediments to sink structures resting on the chamber into bottom sediments. This construction process was used for constructing seven pneumatic caisson lighthouses in Chesapeake Bay, which are now fishing legacies thanks to the extremely difficult, hazardous, and backbreaking work by the sand hogs. Chart 1 identifies and shows the location of caisson lighthouses and other light structures scouted here as fishing destinations.

When fishing caisson structures, all we see is the caisson and the light structure on top of it. There’s nothing on the chart to give away that subsurface rocks may be there, and in some cases, a lot of rock. Cartographers didn’t put riprap symbols on former paper and raster charts for caisson lights in contrast to riprap symbols charted for screwpile lighthouses and skeletal steel towers. So, before sonar scanners, we had to learn the hard way—by snagging.

Consulting historical construction details sometimes provides a better understanding of a caisson light structure’s fishing attributes. But available historical records aren’t complete. Rock is present at some lights where rock isn’t documented. After digging deeper into the history of the Bay’s lighthouses, the following is what I found.

Huge caisson “sparkplug” style lighthouses offered a stable manmade outpost designed to withstand storm waves and winds, strong currents, and ship strikes. Initial caisson lighthouse construction involved fabricating a wooden box caisson, fastening the lower courses of curved cast-iron caisson plates, floating the caisson assembly to its designated location, weighting it down by progressively filling it with concrete and rocks and sand, adding layers of cast iron plates, and backfilling with more cement and rock as the caisson settled to the bottom. They were then jetted into the bottom with water jets and pumps and held in place by their own weight. Although most caisson lighthouses survived winter ice damage they have one weakness: susceptibility to scour.

Pneumatic caisson structures followed the same general construction method except that the chamber served as a pressure chamber with an air lock for the manual labor of digging the caissons into the bottom. Caisson layers of curved cast iron plates were progressively added as the structure was dug deeper into the bottom. Once the excavation depth was reached, the chamber and subsurface voids were filled with cement and stone to keep the structure from floating. Riprap was placed around some to protect against scour. So, what structure is at the caisson lighthouses to fish?

Site 1 Craighill Channel Lower Range Front Light (1873) was the first caisson-style lighthouse constructed in the Chesapeake Bay using the float in, sink, dredge in, and fill technique. It’s constructed on deep, soft bottom which precluded placement of rock. The biofouled vertical sides are the fishing structure.

Site 2 Baltimore Light (1908) pneumatic caisson sits off the mouth of the Magothy River. Coast Guard historical records report that the chosen site was found to have 55’ of semi-fluid mud above a stable sand layer. A storm pushed the caisson over onto its side during initial construction and the contractor went out of business. The caisson was eventually righted and dredged down to 82’ below the surface where it encountered sand and sits on 91 pilings driven into the bottom. The biofouled caisson iron plates are the fishing structure at this lighthouse.

Site 3 Sandy Point Shoal Lighthouse (1883) sits on a wooden caisson foundation which was sunk only three feet into the bottom. We learn from the Coast Guard’s historical registry nomination that during a 1901 routine inspection, including the taking of soundings around the station, an extensive scour in the immediate vicinity of the lighthouse was discovered below the foot of the caisson. Within a few weeks had enlarged nearly necessitating an emergency treatment. In 1902 about 670 cubic yards of riprap was laid around the foundation to prevent further bottom scouring.

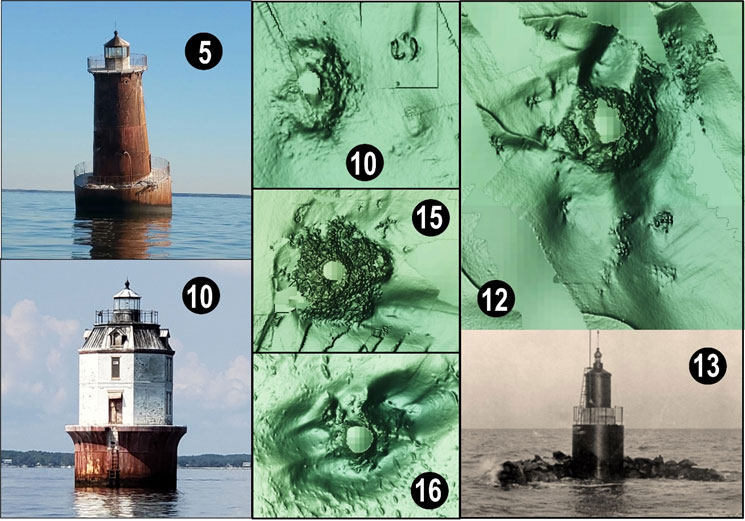

Huge rocks are around the base and also away from the base (Image 1). There’s also an object that looks like the wreck of a small open boat nestled against a large rock. When fishing here, in addition to fishing the caisson, try jigging the rocks away from the caisson. Using older, beat-up jigs is a good idea; it hurts less when they are lost.

Site 4 Bloody Point Bar Lighthouse (1882) is an entirely different type of caisson structure. This is a fabricated cast iron lighthouse and caisson in a single structure with the bottom filled with cement. The structure leans slightly towards the northwest as a result of scouring that occurred in 1883. Riprap was placed on the northwest side but disappeared, possibly settling into soft sediment. Heavy brush mattresses were then laid around the base to stabilize the bottom and held in place by a covering of small stones. In 1885, 760 tons of large rock were placed around the base. The scour apron was visible at low tide at that time, but today depths are charted at seven feet. The light structure and rocky bottom sometimes attract stripers and are worth checking out when passing by.

Site 5 Sharps Island Lighthouse (1882) is another fabricated “coffee-pot-style” cast iron caisson and lighthouse structure. It sits in sand and has no rock protection. Pressure from heavy winter ice in the 1970s pushed the light over leaving the leaning tower we see today. The now long-abandoned caisson has cracks and is in poor condition. A cast iron ladder broke off on the southwest side and is laying on the bottom. Ebb currents and northerly winds create strong currents around the base. Yet, there doesn’t appear to be much if any scour. Tossing a live spot on a weighted line on the up-current side and letting it fall back to the light sometimes produces. Some seasons speckled trout have also been known to gather around the lighthouse in the heat of summer.

Site 6 Southeast of the Sharps Island lighthouse ruins is an icebreaker that protected the former Sharps Island screwpile lighthouse until heavy ice swept the structure away with the keepers inside during 1881. The wooden house floated for five miles before grounding, enabling the keepers to escape a watery grave. The “detached” icebreaker consisted of three wrought-iron screwpiles that were braced together and 200 cubic yards of riprap placed around them. The now submerged rockpile is just east northeast of the navigation marker. Rockfish and bluefish commonly cruise the area but there are only a few feet of water over the rocks, so approach cautiously.

Site 7 Hambrooks Bar Warning Daybeacon in the Choptank River was a cement-filled caisson light structure that has rocks around the cylinder as scour protection. The abandoned structure was planned for demolition, but that hasn’t occurred. Some of the rocks cover at high water levels. So, there’s a rockpile to cast to.

Site 8 Hoopers Island Lighthouse (1902), not to be confused with Hooper Strait Light, is a pneumatic caisson structure which is surrounded by riprap to prevent scour. During construction 300 tons of riprap were placed and augmented by a second placement of an unspecified quantity of stone.

Site 9 Over at Hooper Strait Light, which is now a skeletal steel structure that replaced a screwpile lighthouse, there’s a submerged rockpile just northwest of tower. Its location isn’t specifically charted, although the riprap symbol on paper and raster charts provided a general warning. Based on the rockpile’s location relative to the light structure, down-Bay ice floe movement through the strait, and its round mound shape, a best guess is that the rockpile was an icebreaker rather than stone placed under the former screwpile lighthouse. However, if the latter, then that would be where the light was located. Approach carefully from a safe direction.

Site 10 Point No Point Light (1905) on the west side of the Bay off Point No Point suffered numerous mishaps during construction of the pneumatic caisson structure. At one point, the wooden caisson with three tiers of iron plates attached was moored to a temporary pier which collapsed during a gale. The second and third tiers broke off. The caisson floated down the Bay before being recovered off the Rappahannock River. After repair, the caisson was towed to the site and sunk, and secured in some manner with 225 tons of riprap. Since sand hogs had to work inside the chamber, rocks were probably placed around the caisson to keep it from being displaced. Although the caisson survived a heavy ice year during construction, the replacement construction pier didn’t. An air compressor, boiler, cement, and stone were lost when it was carried away.

At least three objects are about 40 yards northeast of the caisson. The two curved features on the bottom are charted as an obstruction and suggest they’re the lost cast iron plates. A circular mound is about 45 yards to the southeast, possibly the site of the lost construction equipment and materials. So, there are multiple spots here to check for fish. If they’re not productive, there’s both individual and massive artificial reefs to the southwest inside the Point No Point Fish Haven.

Site 11 Solomons Lump Lighthouse (1895) pneumatic caisson has 300 tons of riprap scour protection in addition to the caisson.

Site 12 Smith Point Lighthouse (1897) has a pneumatic caisson plus scour protection. About 825 tons of rock mined from Virginia’s Occoquan River were deposited around the base, but much of this rock has been displaced away from the lighthouse itself. It continues to provide excellent marine habitat.

Site 13 Pungoteague Light (1908) was another small concrete filled caisson light which is now a ruin. It was protected by a rock breakwater on the west side. All that’s left is a listing caisson and the now submerged rockpile.

Site 14 Wolf Trap Light (1894) has the pneumatic caisson and 300 tons of scour protection.

Site 15 Thimble Shoal Lighthouse (1914) is a pneumatic caisson structure protected by a massive quantity of riprap. Some rock displacement has occurred and a large scour developed off the southeast side, but most of the rock is still around the caisson.

Site 16 Middle Ground Lighthouse (1891) at Newport News has a very deep foundation protected by about 1000 cubic yards of riprap. The light receives the full force of flood and ebb currents, and massive scour holes have developed. Much of the riprap has been displaced. The structure is in the center of Virginia Marine Resources Commission’s Middle Ground Reef, which has been extensively developed with demolition materials, reef balls, and other reef structures.

Most Bay caisson lighthouses were declared surplus by the Coast Guard and sold by the General Services Administration to private bidders or abandoned. However, the Coast Guard retained an easement for a navigation lighting at most. Each of the lights described offers fishing opportunities. Productivity varies with conditions, but each deserves a place in your prospecting playbook.

- By Wayne Young. As well as being a regular contributor to FishTalk, Wayne Young is the author of multiple books detailing wrecks and fishing reefs in the Chesapeake Bay, Delaware Bay, and beyond. All are available at Amazon.com, and you can find his Facebook page at “Chesapeake Bay Fishing Reefs.”