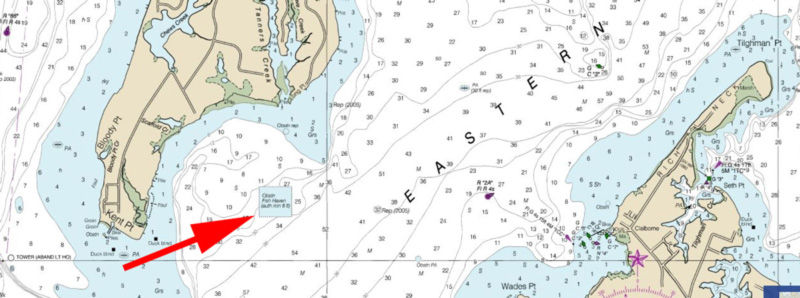

“Fishing in Maryland,” once an annual must-read for all who enjoyed Chesapeake Bay fishing, has been out of print for many years. Find an old copy, however, and you’ll see that one of its fishing maps showed a spot called Holaga Snood in Eastern Bay. Holaga what? Hollaga Snood (the more common spelling) is a traditional name for what is officially “Natural Oyster Bar 8-5” east of Kent Point. However, Hollicutts Noose is the name of the charted fish haven (sometimes spelled Hollicut’s Noose). Huligat’s Snooze and Hooligan’s Snooze are also sometimes used as local names for the fish haven.

From the title of the 1957 duck hunting book “Hollica Snooze” found by Guide Richie Gaines, as reported in the April 2017 edition of Chesapeake Bay Magazine, “snooze” may have been part of the original local name. The shape of the shoreline is said to have reminded Kent Island settlers of a harlequin’s nose. If so, somehow, perhaps by local dialect, harlequin became Hollica. How did “nose” become “snooze”? Maybe the “s” at the end of harlequin’s nose got misplaced. No one knows for sure who or what Hollaga and Hollicutts refer to, but a “snood” is a short line by which baits are attached to a trotline, thus Hollaga Snood is the most nautical of the bunch. Names aside, what really matters is that the fish haven has substantial, heavily encrusted artificial reef structures that attract bait and predators. Plus, the reef can often be fished by recreational boats when a nor’ wester makes it too nasty to go out on the main stem of the Bay.

Reef records say the first artificial structures at this fish haven were tire units placed in 1968. The model for these reefs were prefabricated tire units put in the Cedarhurst Fish Haven off Shady Side in 1965. Each tire unit consisted of 10 tires having diameters of two to four feet. The tires were weighted with concrete and held together by wire. This general approach was used for tire units at other Maryland state reefs during the late 1960s and also in the early 1990s.

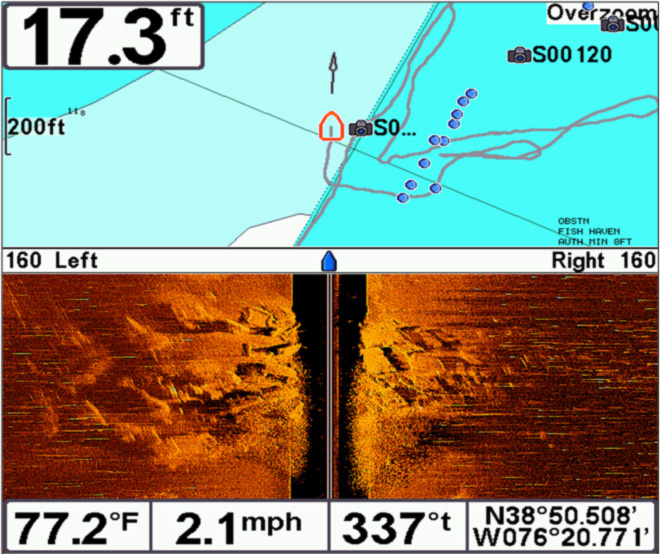

Tire units in Maryland’s Bay reefs are small and finding them is difficult. Side-scan sonar-like coverage from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Bathymetric Data Viewer (BDV) for some state reefs suggests most tire units may be covered by sediment. Bound tire units at Hollicutts Noose are an exception. A 1990s underwater picture by John Foster, one of the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) former reef managers, shows a tire unit standing upright and heavily encrusted with marine growth.

Using side-scan sonar several years ago, I found a bottom feature that has a tire-unit profile on the west side of the fish haven. Although this reef provides minimal structure, it is just south of heavily encrusted remnants of two bridges and a pier, other concrete materials, and a cut up steel tugboat. I recalled seeing an old side-scan sonar image that suggested this massive reef straddled the western side of the charted site boundary. This is also what I found with my sonar scans and GPS positions. My fishfinders and down-looking sonars also recorded structure projecting up to eight feet off the bottom and minimum clearances of about 11 feet.

The boundary anomaly is probably an artifact of using Loran C to position reef materials prior to the mid-1990s. Loran was a significant advance in navigation technology, but it was primarily intended for ocean navigation. It had an advertised accuracy better than a quarter of a nautical mile. There was also an interpolation error factor when transferring Loran readings to paper charts. The error factors means that reef boundaries and positions of reef materials recorded using Loran-C could be a hundred or more yards away from their actual geographic coordinates. So, Loran-C error is probably why the rubble reef at Hollicutts Noose straddles the western boundary.

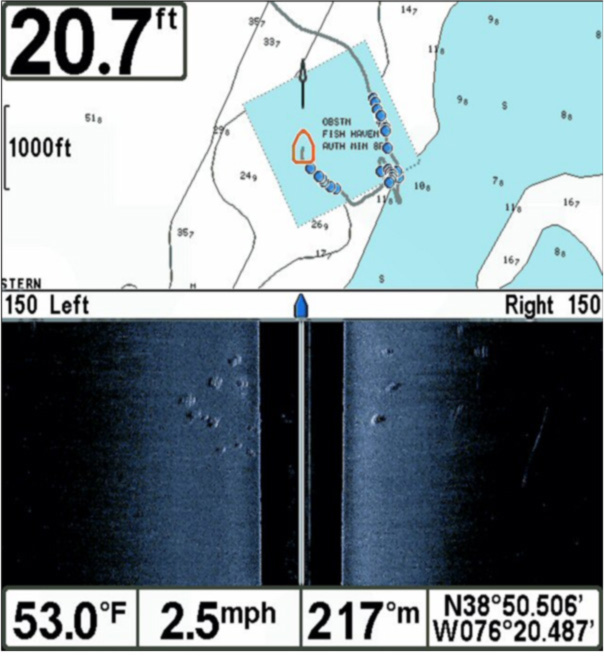

Hollicutts Noose was one of two sites where infamous hook-snatching open concrete frames called “cubes” were pushed overboard. Old records indicate even more, well over a thousand, were dumped in the Plum Point Fish Haven. Just envision a one-cubic-yard box framed by concrete four-by-fours with the outside of the box removed so only the frame remains. Although well-intended, the concrete formula and smooth sides didn’t work well as substrate for attachment of marine organisms. Cube design didn’t provide much cover for bait and fish, either. The cubes at Hollicutts Noose are generally scattered towards the middle of the charted boundary.

During my reef management service, the Maryland Charter Boat Association provided advice about which state reefs to develop and how best to configure available material. Redeveloping Hollicutts Noose was suggested to take advantage of shelter on the east side of Kent Island as a fishing destination for recreational fishermen. Hollicutts Noose subsequently became one of the first fish havens where reef balls were installed to improve habitat value and fishing opportunity. These dome-shaped structures are made with specially formulated and textured concrete. The majority of the weight is towards the bottom third of the unit, providing stability. Holes with curved sidewalls in the side and a top hole enhance circulation around each unit. Thirty-two reef ball in several sizes were poured by the Maryland Environmental Service (MES) and the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) during volunteer reef building events at Discovery Village in Shady Side.

Projects like these would not have been possible without grant support and volunteer labor. The Abell Foundation, ExxonMobile Foundation, Constellation Energy, and MES provided grants that assisted with the cost of materials, staff labor, and deployment. Most of my work hours were charged to accumulated comp time as a donation to the program. It was a lot more fun building reefs than doing yard work!

The first 32 reef balls were placed in a circular pattern of small clusters towards the east center of the site in 25 feet of water. Most were placed just above the drop-off that runs diagonally from northeast to southwest. I deployed a small video drop camera while Tom Humbles operated the video recorder, and we observed a striped bass checking the reef balls out just after CBF’s Patricia Campbell lowered them to the bottom. Another 69 reef balls were later placed in two groups near the northwest top edge of the site. Shallower water there gave juvenile oysters that CBF had set on these reef balls at their Shady Side hatchery a greater chance for survival.

The primary spots to check out for recreational fishing at Hollicutts Noose are the massive reef along the western boundary, and the three reef ball deposits. The northern reef ball clusters have more units and are easier to find. Although each reef ball is a self-contained reef, groupings of modules into clusters provides more complex structure and mass which draws more bait and predators than does a single or a few units. The reef balls towards the middle of the reef site are closer to the edge of deep water, and are a prospective foraging site for predators.

See our Chesapeake Bay Fishing Reefs Guide to get the lowdown on other mad-made wreck and reef hotspots in the Bay, plus a few in the ocean off the DelMarVa coast.

- Wayne Young is the author of “Bridges Under Troubled Waters: Upper Chesapeake and Tidal Potomac Fishing Reefs,” and “Chesapeake Bay Fishing Reefs, Voyage of Rediscovery.” Both are available at Amazon, and you can find his Facebook page at Chesapeake Bay Fishing Reefs. Look for his new books, “Phantoms of the Lower Bay” and "Hook, Line, and Slinker."

Sign up here to get the weekly FishTalk Chesapeake Bay and Mid-Atlantic fishing reports in your email inbox, every Friday by noon.