There’s nothing plain about three plane wrecks in the Chesapeake Bay, which have turned into fishing reefs. One went down in 1944, another crashed in 1945, and the third in 1989. Other plane crashes in the Bay region are sure to be out there, including one rediscovered in 2018 sitting in a marsh pond on Wroton Island, a remnant of 1940s test flights from Naval Air Station Patuxent. But, the three in the Choptank and main-stem Bay are of particular interest because they weren’t salvaged and their wreckage became unintentional artificial reefs. All three are visible on side-scan-like sonar images available using the National Atmospheric and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Bathymetric Data Viewer (BDV). Two are clearly distinguishable as aircraft. One, known as the Choptank seaplane wreck, is a light tackle fishing destination.

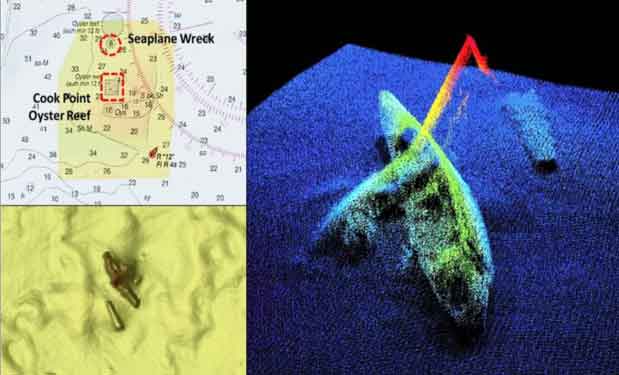

From a fisherman’s perspective, the seaplane wreck is well positioned on the northwest corner of a historic oyster reef. A charter captain favorite hotspot for years, the structure was deteriorating substantially towards the end of my service as artificial reef program manager for Maryland’s Bay reefs. Could we redevelop the site as an artificial reef, considering its popularity and productivity as an accidental fishing reef? “Don’t know” was our reply, but we felt it was worth a good look. So, we began exploring the addition of a new reef to the program. It was 2004, and environmental rules and regulations had evolved greatly from the early days of artificial reef development. During my time as program manager, the Maryland Bay artificial reef program was barely hanging on in the absence of dedicated funding. Maryland Environmental Service (MES) had taken it on as a self-supporting, not-for-profit enterprise when the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (MDNR) discontinued supporting the program with appropriated funds and fishing license fees, as a budget austerity measure. Nevertheless, redeveloping the reef was put on our future to-do list. About this time, I left the program for Coast Guard civilian service in port safety and security to help with ramp up of port-level anti-terrorism measures after the 911 attacks.

The reef program crawled along for a few years until it was reconstituted as the Maryland Artificial Reef Initiative (MARI). Eventually, redevelopment of the seaplane wreck evolved into an oyster restoration initiative piggy backed on a Maryland DNR oyster restoration project at the Cook Point Oyster Sanctuary. More on that later, but first the plane wreck.

The seaplane wreck occurred during a 1944 U.S. Navy training flight. The plane was a PBM-3 Martin Mariner patrol bomber, a seaplane, bearing the Bureau of Aeronautics number 6672. Fortunately, it crashed with no fatalities. The wreck isn’t intact. The top of the fuselage was cut open, suggesting possible salvage efforts, although none are reported. Both engines are missing. The tail and the port wings broke off. The latter lies alongside and rises to a least depth of about seven feet. Least depth by the fuselage is about 30 feet.

South of the seaplane wreck is the Cook Point Oyster Sanctuary and the Cook Point Oyster Reef. The oyster sanctuary is charted. Structure consists of a series of oyster shell piles. A large number of small reef balls, many with hatchery set oyster spat on them, were deposited in the sanctuary on and around the shell piles. The reef balls were poured locally with volunteers by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation and Coastal Conservation Association (CCA) chapters in Maryland and Northern Virginia. This reef is a hotspot well worth putting on your list. It’s also a spot to check for white perch, spot, and anything else that happens to swim by. South of the sanctuary are a series of rectangular-shaped constructed oyster bars. These are relatively level and rise but a foot or two off the bottom, a typical configuration for Maryland oyster restoration projects.

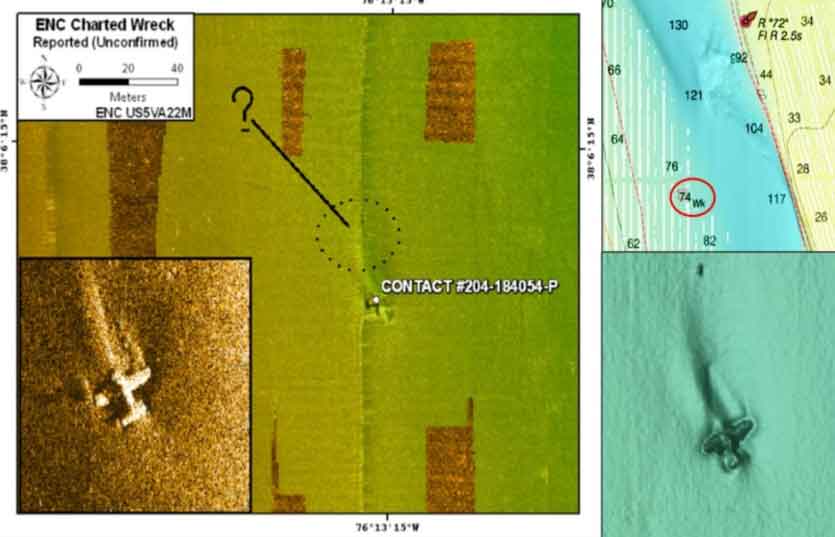

The second plane wreck was found during a NOS hydrographic survey performed by David Evans and Associates in 2010. The find was documented in National Ocean Service (NOS) Descriptive Report H12239 (2010). Subsequent investigation by divers from the Naval History and Heritage Command and the Institute of Maritime History in 2017 determined that the wreck was probably the Grumman Bearcat that was lost in early 1945 during a test flight. The 23-year-old aircraft carrier combat veteran serving as test pilot was lost and not recovered. Down about 74 feet the wreck is not considered a hazard to navigation, however, it is also too deep to serve as productive habitat in the Bay environment. However, it’s a great target for testing high-definition recreational sonars.

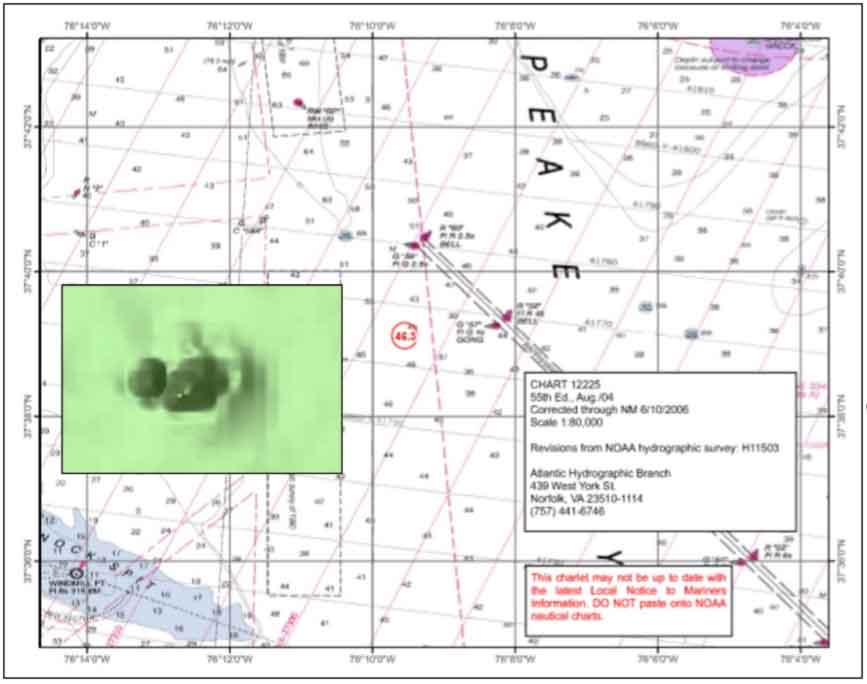

The third plane wreck which occurred in 1989 involved a Gulfstream American single-engine light aircraft. A student pilot was on a cross-country round-robin flight when oil pressure dropped and the engine lost power. He was able to successfully ditch the plane off Windmill Point. The plane sank after about 20 minutes. After swimming around for about 40 minutes, the pilot was rescued by a sailboat. A NOS field team located the wreckage during a hydrographic survey. This is a very small wreck, maybe 22 feet by about 24 feet. According to NOS Descriptive Report (DR) H11503 (2006), it rises about eight feet off the bottom. Although the position is known and water depth is fishable, the small size works against the wreck as a fishing hotspot. However, there is a rugged shelf with a low-relief natural edge to the northeast, just west of Rappahannock Shoal Channel between Channel Buoy G 59 and G 57, so there are multiple options at hand in the immediate area.

There’s also a fourth “airplane wreck” that may or may not have anything to do with airplanes. A tautog tracking study conducted by Jon Lucy and M. Arendt in 2000 for the Virginia Institute of Marine Sciences refers to an obstruction about two miles southwest of Cherrystone Reef as the “Airplane Wreck.” Under a charted obstruction circle are three piles of material consisting of 18 to 20 objects with at least depth of 35 feet. An Internet search for an aircraft wreck in this location was negative. The structure presents as piles of oblong blocks, which is consistent with the Lucy and Arendt report that it consists of concrete rubble. Who knows why the site is known as the Airplane Wreck? The structure is probably an early, unrecorded artificial reef, one of the “Bay Bandits” revealed in “Chesapeake Bay Fishing Reefs: Voyages of Rediscovery” (Young, 2020), and in Cherrystone Reef and the Bandit. All are well-worth putting on your go fish it list of hotspots—and that’s the plane truth.

Author Wayne Young is the author of “Bridges Under Troubled Waters: Upper Chesapeake and Tidal Potomac Fishing Reefs,” available at Amazon.com. You can find his Facebook page at Chesapeake Bay Fishing Reefs.

Sign up here to get the weekly FishTalk Chesapeake Bay and Mid-Atlantic fishing reports in your email inbox, every Friday by noon.